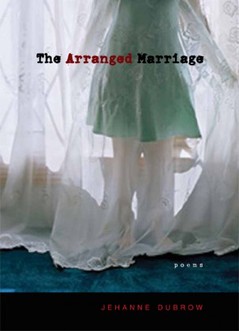

I have been a fan of Jehanne Dubrow's work since I read The Hardship Post (her first poetry collection) five years ago, so I was excited to find The Arranged Marriage delivered to my doorstep just last week. In her newest collection, Dubrow takes on the violence of the past in a series of biographical work from her mother's life. Intertwining narrative prose poems (told mostly in third person point of view) with ekphrastic poems, she shows the reader that the past never leaves us no matter how much we try to paint our lives in linear lines.

Dubrow, as the daughter, is telling her mother's story and besides her own poetic choices (with both language and syntax) there is very little of the poet within this book. Still, there is one poem, "The Blue Dress" that describes a young narrator, "tired of playing dollies and Let's Pretend" who looks through a dresser drawer and discovers a photograph album with pictures she has never seen: "In each photograph, my mother's face was water just before a stone drops in." There's an epiphany moment where the narrator muses, "That our parents have lives before us is a secret we close in a dark compartment."

It's this "dark compartment" of her mother's life that is explored in The Arranged Marriage -- a compartment that is full of violence, secrets, and silence. From the start, we see the tension start to build in the narratives as the first poem, "The Handbag" opens with the threat of violence: a woman contemplates the idea that her purse, one that is "deep enough to confine a bowling ball" could be used as a weapon against the man who is holding her hostage. This man, however, is not afraid, and indeed is only thinking about, "Spaghetti. Meatballs. The meal she'll cook for him."

Poems that explore this attack are intertwined with stories about the woman's first marriage, which is not violent, but cold and often, confusing. Her relationship with her first husband is detailed in such poems as "Bespoke" where the marriage is described as "a custom-made suit" that "fit expensively" yet "scratched her skin, smelled like stale cigar and men playing poker." In another poem, "The Epileptic," the woman says this,"If this is marriage, then it's a mystery -- those pills he takes for headaches, for instance, and when he claims the afternoon is the smell of rotten fruit." Later, she relays a conversation between the two of them, where he calls her "a stranger" and she does nothing but agree. Indeed, it's only after she leaves him that she understands the name for his condition and the reasons why he wears "the pale halo of secrets around him."

Thus, from the beginning, we follow the tension of this woman's life, from the survival of a violent act, to a loveless marriage, to her second life where the events from her past intertwine with day-to-day activities. Years after this incident, memories slip in and out this woman's life. In one poem, "My Mother Wonders---" she contemplates the idea that a dog may have helped rescued her from her attacker. In another poem, "Shot Through with Holes," even a benign setting becomes a place of fear. At Upland Terrace, the scene is described as relatively peaceful, with the "worst menace" being a bird "that pecked the neighbor's cat." There are also raccoons around, with "brave ones" that actually climbing the second story to look into the family home. Still, there is a moment when the mother comes home to an open door -- a sign that perhaps an attacker was near -- that she is again flung to the past, even when the police say, "Ma'am, there's nothing here."

While many of the poems in this collection are narrative, others are ekphrastic poems, works based on visual pieces of art. "The Leap" is based after the 1967 Thriller Wait Until Dark and offers a poetic summary of the climax of the movie where Audrey Hepburn's blind character attacks her stalker. Another poem, "Eros and Psyche" offers a critique of a sculpture by Antonio Canova, and perhaps a critique on mythology itself, with the words, "From this angle the knife is hidden, although it's there, the way an arrow is always shooting through this story." In different ways, these poems also take on the subject of violence, whether it's found in the shadows of an old film, or the smooth texture of a sculpture.

Dubrow's work shows us that history, even personal history, is not linear. Whatever is part of our past stays with us forever, often finding us in unexpected places. This history may slink in through an unlatched door. It may find us in a grocery store or a bedroom. It may get snagged in the zipper of a pencil skirt. It may catch us in a newspaper headline or a work of art. It is never truly pushed behind us.

The Arrange Marriage is part of the Mary Burritt Christiansen Poetry Series published by the University of New Mexico press. For more information about this book (and Jehanne Dubrow's other collections), visit her website.

Dubrow, as the daughter, is telling her mother's story and besides her own poetic choices (with both language and syntax) there is very little of the poet within this book. Still, there is one poem, "The Blue Dress" that describes a young narrator, "tired of playing dollies and Let's Pretend" who looks through a dresser drawer and discovers a photograph album with pictures she has never seen: "In each photograph, my mother's face was water just before a stone drops in." There's an epiphany moment where the narrator muses, "That our parents have lives before us is a secret we close in a dark compartment."

It's this "dark compartment" of her mother's life that is explored in The Arranged Marriage -- a compartment that is full of violence, secrets, and silence. From the start, we see the tension start to build in the narratives as the first poem, "The Handbag" opens with the threat of violence: a woman contemplates the idea that her purse, one that is "deep enough to confine a bowling ball" could be used as a weapon against the man who is holding her hostage. This man, however, is not afraid, and indeed is only thinking about, "Spaghetti. Meatballs. The meal she'll cook for him."

Poems that explore this attack are intertwined with stories about the woman's first marriage, which is not violent, but cold and often, confusing. Her relationship with her first husband is detailed in such poems as "Bespoke" where the marriage is described as "a custom-made suit" that "fit expensively" yet "scratched her skin, smelled like stale cigar and men playing poker." In another poem, "The Epileptic," the woman says this,"If this is marriage, then it's a mystery -- those pills he takes for headaches, for instance, and when he claims the afternoon is the smell of rotten fruit." Later, she relays a conversation between the two of them, where he calls her "a stranger" and she does nothing but agree. Indeed, it's only after she leaves him that she understands the name for his condition and the reasons why he wears "the pale halo of secrets around him."

Thus, from the beginning, we follow the tension of this woman's life, from the survival of a violent act, to a loveless marriage, to her second life where the events from her past intertwine with day-to-day activities. Years after this incident, memories slip in and out this woman's life. In one poem, "My Mother Wonders---" she contemplates the idea that a dog may have helped rescued her from her attacker. In another poem, "Shot Through with Holes," even a benign setting becomes a place of fear. At Upland Terrace, the scene is described as relatively peaceful, with the "worst menace" being a bird "that pecked the neighbor's cat." There are also raccoons around, with "brave ones" that actually climbing the second story to look into the family home. Still, there is a moment when the mother comes home to an open door -- a sign that perhaps an attacker was near -- that she is again flung to the past, even when the police say, "Ma'am, there's nothing here."

While many of the poems in this collection are narrative, others are ekphrastic poems, works based on visual pieces of art. "The Leap" is based after the 1967 Thriller Wait Until Dark and offers a poetic summary of the climax of the movie where Audrey Hepburn's blind character attacks her stalker. Another poem, "Eros and Psyche" offers a critique of a sculpture by Antonio Canova, and perhaps a critique on mythology itself, with the words, "From this angle the knife is hidden, although it's there, the way an arrow is always shooting through this story." In different ways, these poems also take on the subject of violence, whether it's found in the shadows of an old film, or the smooth texture of a sculpture.

Dubrow's work shows us that history, even personal history, is not linear. Whatever is part of our past stays with us forever, often finding us in unexpected places. This history may slink in through an unlatched door. It may find us in a grocery store or a bedroom. It may get snagged in the zipper of a pencil skirt. It may catch us in a newspaper headline or a work of art. It is never truly pushed behind us.

The Arrange Marriage is part of the Mary Burritt Christiansen Poetry Series published by the University of New Mexico press. For more information about this book (and Jehanne Dubrow's other collections), visit her website.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed